3

Eyes West — to Younger Beds

By 1946, our work around Ernest was beginning to

play out, and I had begun to toy with the idea that we should

move our fossil hunting to areas that were

too far to walk to and too rough to

drive back and forth every day. This would be new territory to us but one that Paul Miller and George

Sternberg had worked over along the

Wichita River before Lake Kemp had been put in in 1917. As things turned out, 1946 was a good time to think of

a new base camp, for this was the year that Ernest's house burned down. We did spend part of that season in

his pasture, but we also explored the area to the west with his help.

The house burned while he was riding fence and,

of course, no one was around to see it go or try to

stop it. His mother had been living with him

for a time and, now and then, one or another of his sisters would help

out. All had left, but not before tidying up and putting up curtains. Ernest,

used to some help, apparently was careless

and while he was away the wind likely

blew the curtains into the flame of his gas refrigerator and started the fire.

I didn't know about the house until 1 came into

his pasture about 11:30 A.M., just down from Chicago. I found Ernest and another

cowboy sleeping in the garage on makeshift beds. It was 100 degrees plus and they were sleeping it off. Ernest rolled over when I punched him and exposed a completely,

momentarily horrifying, red side, undershirt, pants, skin and all. The dye on the coverlet was not sweat proof!

He looked downright awful and his half-opened

eyes pretty well matched his red half. As usual, no

greeting, just as if I had been there all along.

"Where's your house?" I asked.

"Burned down," he muttered. "Took my goddamned new suit. Doc," he continued, "you goin' to

town?" I had just come from town, but said I could. "Go to the drug store," he managed. "See the owner, tell him

Ernest's sick, needs some medicine." He sat up, scrawled out a "check" on a piece of brown paper,

putting on the name of the bank and

town, and scribbled the amount. Signing it, he gave it to me to pay for the medicine. I drove back to town fully expecting to pay for the medicine out of my own

pocket. The county was dry by then, so

I was curious about what I might get.

It turned out to be a pint of under-the-counter gin and the druggist happily took the check, which I gave him

hesitantly. About three o'clock I got

back to Ernest's place. His friend had

somehow gotten away Ernest uncapped the gin and took about half of it in one swig. He downed the pint

in a few gulps, while I cringed. A little water and he was up and about,

feeling better. All I could think

was that these cowboys are rough and tough.

Living alone and riding his pasture, Ernest, of

course, knew his range well. He was curious about everything on the range and

had developed a crude sense of biology that stood him in good stead. Cattle, coyotes, rabbits and all such mammals he understood.

"Like people," he told me once,

"when they fuck, they get young'uns."

Snakes, lizards or scorpions didn't intrigue

him much, except that some stung or bit. The

striped grass lizard, Cnemidophorous, was a scorpion, and the scorpion a stingin' lizard.

Rattlesnakes were just for killing. Birds came closer, especially chickens. He kept a few hens for eggs. Their sex habits were

worthy of interest.

I got this story from Professor Romer, who

dropped in on Ernest many times and knew him well.

"Professor," Ernest asked, "do

you know about animals and birds?"

Romer, a professor of biology and anatomy at

Harvard, allowed as how he did.

"Well," Ernest went on, "I've been

watching my goddamned chickens for a long time

now. Did you know a hen don't have to be

fucked to lay an egg?" A sound observation, Romer granted. Another time, I was at the cabin when Ernest came

in with a squawking, jumping bag, containing two roosters.

"Doc," he called over, "you see

them hens there? I got two het up roosters in

this tote-sack. They ain't never seed a hen and them hens

ain't never seed a rooster. Let's see what happens."

So he dumped out the roosters, whose feet began

going before they hit the ground. No niceties, no

courtship gestures, just plain rape. Before they

knew what was going on the unsuspecting hens were

tagged and lit out, with their own indignant squawks, for the mesquite with the

roosters in hot pursuit. By dusk three hens and two roosters were in

the chicken roost, seemingly happy with

affairs, with the roosters on the top rung and the hens on the bottom. Two hens never came back; probably the coyotes got them.

Like most persons who live on the land, Ernest

was a conservationist, taking what he

needed, but not destroying the land's capacity to

provide for all. But when rules seemed unreasonable,

they were to be circumvented. The Waggoner Ranch is a game preserve. Rabbits were fair game, but the big "blue" quail and wild turkeys were

rigorously protected. We once even received a caution for shooting bullfrogs

for food. The ranch had its own game

warden. Occasionally Ernest wanted quail and it seemed right to him that he

should trap them for his own use. Rabbits

were beneath his dignity. Turkeys, too, were a

delicacy, especially if forbidden.

One morning, while we were still there, Ernest

left on his dappled mare with his shotgun, rather than his old rifle which he usually carried strapped onto his saddle. He told me that he had three shells and that he was going to get a turkey

from the wild flock to the north of his

cabin. I had seen him hit a rabbit from a moving car with his rifle,

but also seen him miss a knothole target in

the yard from 50 feet while standing still. After that he adjusted his sight

with a hammer! According to his philosophy there was nothing wrong with

us having a turkey or two, but I was a bit

more dubious, or apprehensive, after the

bullfrog incident.

About four o'clock, when the hot, drying day had

brought us in early, Ernest came back with one shotgun shell left and three

turkeys, ranging from about six to ten pounds. In a few minutes they were

cleaned and in the monstrous refrigerator. Feathers,

of course, were all over the yard and would fly up in our faces when the sandy, gusty wind blew.

In about an hour, sure enough, the game warden

rode up. He patrolled the whole ranch,

the whole half million acres, and my education

in Texas ways was never up to knowing just how he spotted illegal activities. Helicopters were still a few years away. Whenever we would be out of our usual haunts he would seem to show up, just checking on who we were. It was

more than coincidence, I am sure, that he rode up just when he did, neither

too soon nor too late.

"Ernest," he started out, "I got

some reports of shooting up north of here.

You know anything?" "Can't say I do," from Ernest.

The game warden, "You know that flock of

turkeys up the way?"

"Up thar som'eres."

"Well, someone's been shooting at them.

That's a jail offense."

"Should be," said Ernest.

All during this conversation, of course, gusts

of wind were blowing turkey feathers all

about, right in our faces.

"What's that, over there?" asked the

warden pointing to a wooden apple box tilted up on a stick with a string

attached to it.

"Rabbit trap," replied Ernest. "Quail trap."

"Come on over," asked Ernest, moving

toward the trap. "See that fur?"

He pulled out some gray rabbit fur from among

grains of corn. "See, the poor rabbit

caught hisself on that nail in the box before I got him

out. Can't get no quail near a box like that."

"Well, you know trapping quail means a

fine and jail too," the warden told him.

"Yeah, I know, and a good thing too. Don't

want no poachers on this ranch," came back Ernest,

closing off the conversation.

|

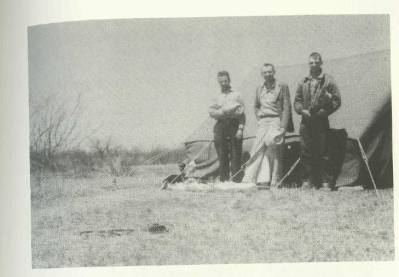

Figure 8. Camp at

Sharvar Tank on the Waggoner Ranch, 1951. Left to right: Neil Tappen, a student

of anthropology. Neil continued on to become a distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of

Wisconsin at Milwaukee. Robert Bader, who after a career in zoology at

the University of Florida, Gainesville,

became Dean of the College of Liberal Arts in the University of Missouri, St. Louis, Missouri.

Robert Sloan, who deserted his early love of invertebrates for a career as a

vertebrate paleontologist and became a professor in the Department of

Geology and Geophysics in the University of Minnesota at Minneapolis. |

Finally — it seemed like an hour to me — the

warden got on his horse and rode to the gate.

While Ernest was opening it, the warden said,

"Ernest, if you hear any shooting, let me know."

"Shore will, got to keep them turkeys safe

from them hunters."

The warden rode off.

Gradually, during 1946 and 1947, our work took

us farther and farther west. We were trying

to find fossils in beds younger than any that had

yielded them earlier and this meant gradually moving away from Ernest's cabin. First we went to Sharvar Tank (Figure 8), some 18 miles west from the main ranch headquarters, called Sachuista, which lies on the

Vernon-Seymour road.

We camped there for parts of two or three

seasons using the water from the tank for everything. Bryan Patterson, then of Chicago, later Harvard, visited us and brought along

the owner of the property he was working on

farther east.

This old gentleman, wise in the ways of the

area, refused to drink from the tank. He noted an over-ripe steer carcass a couple

of hundred yards away and the buzzards that ate on it sometimes flew over the tank losing their cargo. The tank was big, and

cattle drank from it and took care of their other needs in it, but none of this bothered us outlanders. We

drank the stuff and felt fine. Not

the old gentleman. He drank wine which he

had brought. Wise as he was, and I am sure he was really right, Bryan and his group had to leave after two

days because the old man had a serious

case of the "runners."

The last time we camped at Sharvar Tank, Ralph

Johnson and I set up camp and then noted how low the water was. This was during one of the periodic droughts in the region. The drinking did not look too good so we made coffee with the water. Coffee never did much to change the color of the red water, and we would use only red water because clear water meant a high content of gypsum, second cousin to epsom

salts. This time, as usual, the color did not change,

but the taste was terrible. We found out how bad

boiled green algae could be. Not only was that

batch bad, but the coffee pot was ruined, for no end of boiling

and scouring could get rid of that foul taste. We changed plans and began to go six miles out to a line camp and haul our water. We could still squat down to

bathe, but the value of the procedure was dubious.

Talking over "going west" on the

ranch with Ernest turned us to what some people

called Ignorant Ridge (Figure 9). I don't know why this name came to be, and did not find anyone who did. Some didn't even believe that the ridge was called Ignorant Ridge, It lay at the western edge of the Waggoner

property in Knox County, some seven sand-and-red-mud miles north

of Vera and about five miles of sticky

black mud and sand from Gilliland. There were about 20 feet of Pleistocene

gravel, sand and black soil on top

of the Permian beds there and this made for good farming on the gumbo and an abundance of well water. Ernest had told me to go over there and, at

the top of the hill, to look up Ab Covington, who was keeping the west pasture for Waggoner.

|

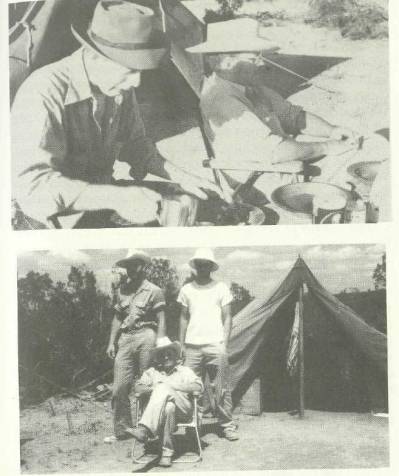

Figure 9.

Top: Camp on Ignorant Ridge. Students slave and bosses supervise or sleep. Bob

Miller was good at dishes but better at the mathematics of evolution. At this time a graduate student,

he went through all the stages up

the ladder at the University of Chicago, becoming a Professor in Geophysical Sciences. Having struggled to teach

me math, Bob left fossils and evolution to become an expert in near

shore wave processes and sediments. Bottom:

Camp at Ignorant Ridge, our home for several years. Left to right: Russ Guthrie, outdoorsman, who with his Ph. D. from Chicago went from

the Permian to become an outstanding student of Pleistocene mammals, their taphonomy and biogeography from

his base at the University of

Alaska. The "boss" in the seat of honor and leisure. Ted Cavender, fossil and recent fish expert who, after his

Ph.D., continued his research at the University of Michigan and Ohio

State University. One of the best men with

a shovel and pick on our crews. |

"You go see old Ab and tell him Ernest

sent you. You say to him, 'How are you, you old son of a bitch.' He'll know I

sent you."

So I did, and Ab did. I was ready to duck, for

Ernest had often told me how this gentle

greeting to strangers had got him in trouble.

But Ab understood and somewhat later we set up camp

on Ignorant Ridge about 200 yards from the house and with a rich supply of water. The water was a problem for a little while until our systems adjusted to its moderate gypsum content, but

thereafter nothing tasted quite so good. The site was beautiful, overlooking the broad valley of the South Fork of the Wichita

River, a richly green valley where the luxurious grass and mesquite fought a never ending battle against each other. The mesquite always won unless controlled by the

ranchers. Cedars — really junipers —

topped the hills and on even the hottest nights a breeze welled up from the

valley. With this move, I didn't see

Ernest for long stays and sort of lost touch with him. One year, soon

after, I found that Ernest had been moved to

the Flippen Creek gate of the ranch, where Byrdie Fergusen, who kept the gate, took care of his failing

health. By summer he had moved to a

house in Seymour. The Waggoner estate, like

many large ranches, was a highly paternalistic organization, taking care of its people, so Ernest was in

no want. Ab Covington also had been moved to Seymour, so he and Ernest had each other for company.

During that summer I went to Seymour to look up

Ernest. He and Ab were at his place and we sat and swapped yarns for a time. Ab's old dog, Dan, one of several from the

ranch, ambled up and flopped on the porch with

a gasp of solid comfort. As usual in the late afternoon that time of

year, clouds had been building up. They

announced their presence with a ripping blast of thunder. Old Dan,

contented no more, slunk into the house,

moving faster than I thought he could.

"Old Dan sure git when it thundered," Ernest allowed. "Didn't used to," from Ab, "but an

old mare I had attracted lightnin'.

Everytime I rode her and a cloud come up, sure enough bolts would start hitting around us. Old Dan finally got so he wouldn't go out with that mare and me.

Finally it got so he just wouldn't go

out at all."

"Had a mare like that," mused Ernest.

"Just seemed to draw a cloud. Had to

git rid of her. Wonder if she ever got hit?"

"That was a while ago," Ernest went on.

"Seems a long time back."

"Yup," said Ab, trying to get back in

the swing of the talk. "Hmm," said

Ernest, and went on. "Brings to mind one evening with a

storm comin' on. We was a bunch of young

bucks settin' on Mrs. Bates' porch, where we was boarding." Ernest

began, keeping Ab out of the yarning. "We was drinkin' beer and every so

often one or another would get up and piss

off the porch. Out come Mrs, Bates and says

'You fellers quit pissin' off the porch.' So," went on Ernest, "we went into the yard and pissed on the

porch." His big, snaggle-tooth

guffaw .... "Pissed on the porch." Another guffaw.

"Pissed on the porch. Ha, ha, ha,

ha . . ., ha . . . ."

Next spring, I heard from Byrdie that Ernest had

been very sick. He was back in Seymour, but

still wasn't doing too well. His whole system was just running down,

complicated by his asthma or, more likely,

emphysema. The story I got is as follows. In the Vernon

hospital the doctors had pretty well given up

on keeping him going and since he had a short time asked what he would

like. Nothing he could ask for could do him much harm. Ernest rather weakly

suggested he would like a good drink of

whiskey. Just where to get it was a problem, for the area was dry.

At that time Robert Anderson, later a prominent

member of the Eisenhower Administration, was Executive

Manager of the Waggoner Ranch, which had its headquarters in

Vernon. He was greatly liked and respected

by the people of the ranch and of Vernon as well, and had aided in reducing the

conflicts of the ranch and town that had long existed. So the hospital asked him if he could procure a bottle of

whiskey, which he did. Ernest began

to feel a little better and with a second bottle was well enough to leave the hospital for Seymour

once more.

I rather imagine, knowing Ernest well, that the

feeling that everything was over for him was

as much to blame for his critical condition as his

obviously bad health. He no longer had his horses, his morning Bull Durham and his coffee. He couldn't cuss and

blaspheme as liberally as he used to, and the old red hill north of his old

cabin, where he wanted to be buried, was far away. There was just nothing to do and his way of life had not

developed any resources away from the land.

As soon as I could I went to Seymour, along with

Nick Hotton, one of my graduate students, to see

Ernest. He was in bed when we got there, about 3:30 in the afternoon. I

suspect that he spent most of his time

lying down. He never read much and, of course, there was no television.

He started to get up, brightening, when we

came in, but we just propped him up on a

pillow.

"How ya doin?" I asked. "Not too good, Doc. Not too good." "Ernest," I said, "Byrdie's told me you have given up

swearing and cussing. Is that right?"

"Smoking too," he replied.

"Seems to get my lungs." Then with the old twinkle in his eyes. "I never did go much for this God stuff, but I'm goin' pretty soon. Don't mind,

grant you, but figured I'd take no chances with

cussin' so I quit." "Must kinda hamper you, doesn't it," I

quipped. "Ain't no one to talk to, nothing to say, no

breath to say it anyhow, so don't make no nevamind."

We chatted together for about an hour about old

friends, Byrdie, his mother and sisters

and my old field partners, Ernie, Bill, Roy,

Mike and the lot. Where were they now and how had they done? Never figured Mike would get out of the bush, he was so short and meek, should have had a flag attached, and so on ....

I never saw Ernest again, for soon he passed on. He had always wanted to

be buried in the red hill near the house on Coffee

Creek by the Old Seymour Road. But, of course, it was not to be. Yet, when I go past the hill, as I do

once in a while now, I feel some

part of him has rubbed off on it, for it seems to have some of the gentleness

and hell raising cussedness of this man resting in its bare red

sandstone and clay.